Description

Duluth is one of the most misunderstood assets I’ve ever encountered; I believe it can compound at 20% or more for 7-10 years. You just need patience and a stomach for volatility. A cast-iron stomach.

The company is debt-free (ignore the weird VIE on their headquarters building that isn’t recourse to them) and will generate substantial free cash flow going forward. The stock price could do anything, but with a long-enough time horizon (which needs to be measured in years), I think it is extremely unlikely that a shareholder won’t make a ton of money (let alone lose money.)

I don’t say these things lightly; if you read my other writeups on VIC, I try to be fairly conservative and circumspect. I’ve just followed this business for 7-8 years (owning it on and off, in varying size, for 4 years) and despite it wrecking my PnL on multiple occasions, I continue to believe it is a phenomenal opportunity for those willing to step back from the noise. It is okay if you don’t believe me… most people won’t. I won’t try to convince you otherwise. Hopefully you at least find the writeup entertaining. You just kind of have to see it for yourself - and if you don’t, that’s OK, there are plenty of other fish in the sea.

Generally, when I have really bad outcomes with a company, I tend to get really angry with management. This one’s different - I think highly of them, even though they’ve done catastrophic things to my returns (multiple times). I say this just because I’m going into this with both eyes open, having both made and lost a lot of money on this stock (more recently the latter.). I use these calculators to arrive at that conclusion:

The Thesis

Duluth is an amazing and underpenetrated brand with ~$650M annual revenue, split roughly 65/35 between e-commerce (called Direct) and retail storefronts (not mall based). They’re known for two things - their hilarious commercials (which you’ve probably seen during a football game), and their functional products.

Duluth doesn’t win on fashion - they win on function. They make things like Longtail Ts (to cover up plumber’s butt), Buck Naked Underwear (very comfortable - my friend can’t stop talking about how much he loves his and honestly it’s getting a bit awkward), Ballroom jeans (not for dancing - they provide extra breathing room for what the name suggests), Fire Hose Pants (which are strong enough to resist the tusk of a charging wild boar), NamaStash NoGa pants (women need pockets too), Alaskan Hardgear winter clothes, and so on. People buy Duluth products because they work; the attention to detail is outstanding and quality is excellent.

As a result, they have stellar net promoter scores. In addition to the thousands of favorable reviews online, I have never personally come across anyone who doesn’t love their products once they’ve tried them - this includes men and women from ages 20 to 75, ranging from couch potatoes to outdoor adventurers. Perhaps my favorite review is from a friend of mine who moved to the Philippines and reports that their cooling Armachillo fabric stands up to years of riding around the dusty, sun-baked third world on a scooter.

According to the best stock research websites, the product focus doesn’t mean that Duluth is totally immune to trends, but it does mean that you don’t have to worry about “fad” or “fashion” risk like you do with most apparel brands. They also have a high mix of basics (socks and underwear are good year-round), so combined with not being fashion-forward, they have less inventory perishability risk than most retailers.

What this means is that over time, there is plenty of whitespace for Duluth to expand. They can expand their product line (as they have done by getting into areas such as gardening and fishing.) They can expand their customer demographic (as they have done by targeting younger and skinnier consumers, as well as women.) They can expand their geographic reach (they don’t have a single store in Arizona or California, and only one in Florida.) They can expand their channels (they currently have no wholesale revenue other than a modest pilot with Tractor Supply). And they can, quite simply, expand their customer base.

Just as a brief thought experiment, Columbia’s DTC business represents about 45% of their revenues.

“Revenues from the direct-to-consumer business represented 45% of VF’s total Fiscal 2023 revenues”

DTC is the hard business to grow - you have to actually attract customers. Wholesale is relatively easy - of course the product has to be good and sell through, but when you’re starting from zero, every door is incremental revenue. Get a new door, get new revenue. Rinse and repeat.

So just for fun, even if we assume that Duluth can never grow its DTC business ever again (despite the fact that COLM/VFC are still growing theirs off a much larger base), Duluth could double the size of its business over the next 10 years by building out a wholesale channel. COLM/VFC have both historically generated 15%+ EBITDA margins, so I see no reason that Duluth can’t generate 10% margins.

That’s really it in a nutshell. Duluth will, at some point in the future, be a much larger company than it is today, with much higher margins. And the market isn’t even pricing it for what it is today. As I write this, Duluth has an enterprise value and market cap in the neighborhood of $250 million. I posit that in 5-7 years, Duluth will post a billion in revenue at 10-12% EBITDA margins. At some pedestrian multiple (say 8x), with some interim cash flow, that’s worth a billion dollars, and possibly quite a bit more.

There is an enormous gulf between the public market’s myopic, quarter-to-quarter view on Duluth, and the underlying value of the brand. Nobody gets it. They’re lumped in with a bunch of me-too retailers with no distinctive or enduring brand value. To understand the thesis and why you should ignore all the noise, you have to understand the history.

The History

Carbone959 wrote Duluth up last December. His intro provides a good start:

Duluth was started by two brothers who came up with a product called The Bucket Boss, a leather wearable bucket in which workers can carry tools. Eventually they grew this into a mail-order catalog business with various products including accessories, tools and storage equipment. It was mostly aimed at workers in construction and other hands-on occupations.

The business was then sold to a Finnish company, which flipped it in the beginning of the 2000’s to Steve Schlecht, owner of a similar business called Gempler’s. Originally his idea was to merge Duluth and Gempler but later he decided to sell Gempler and focus on growing Duluth, which he grew by 100x. Data from the best stock screeners shows that this was accomplished by introducing Duluth-branded apparel, using e-commerce and doing lots of advertising. In 2010 the company started opening retail stores, mostly in the eastern half of the United States. They were taken public in 2015. The Schlecht family currently owns 29% of the equity and Schlecht is now just chairman.

I want to focus more deeply on Schlecht. He wrote a book called The Art of Building a Brand that is required reading if you are considering investing in Duluth. While Schlecht is not per-se the founder (since he didn’t start it), Schlecht is to Duluth what Howard Schultz was to Starbucks - he took a fledgling concept and built it into something much bigger.

Schlecht’s book details the care with which the company has built its brand over time. (I don’t think there’s any chance of them following in the “go woke, go broke” footsteps of Target, Bud Light, and The North Face.) Duluth has sort of followed the reverse path of most companies. Because of his background in the catalog business with Gempler, Duluth originally grew almost entirely through the “direct” channel, via catalogs and e-commerce. The company then realized that stores (none of which are mall-based) served two important functions - marketing / brand awareness as well as a physical location for customers to try on goods (particularly important in building their womens’ business.)

The company has always taken a long-term orientation. That’s not to say that they haven’t made mistakes - for example, at one point, they were opening stores a little bit too quickly and got over their skis. However, one of the reasons they are entirely DTC at this point (you can only buy their products through their website or their stores) is because they wanted to nurture the brand through its infancy rather than simply throwing it at a bunch of doors and seeing what stuck. That is not to say that wholesale is not a massive opportunity; their product would absolutely kill at a Cabela, Scheels, and REI, not to mention all your run-of-the-mill department stores.

The problem is that they are in a sector where people focus almost exclusively on near-term trends, and - to put it bluntly - their near term trends suck. This is irrelevant, and I will explain why it is irrelevant if you stick with me.

Where They Are and Where They’re Going

We’re fond of investments where the numbers look bad while the business is getting better. Franklin Covey (FC) is an example of this, where people thought the management team had lost their minds for a few years - until all of a sudden their investments paid off with a deluge of cash flow. We think Duluth is rather similar (albeit a very different business model.)

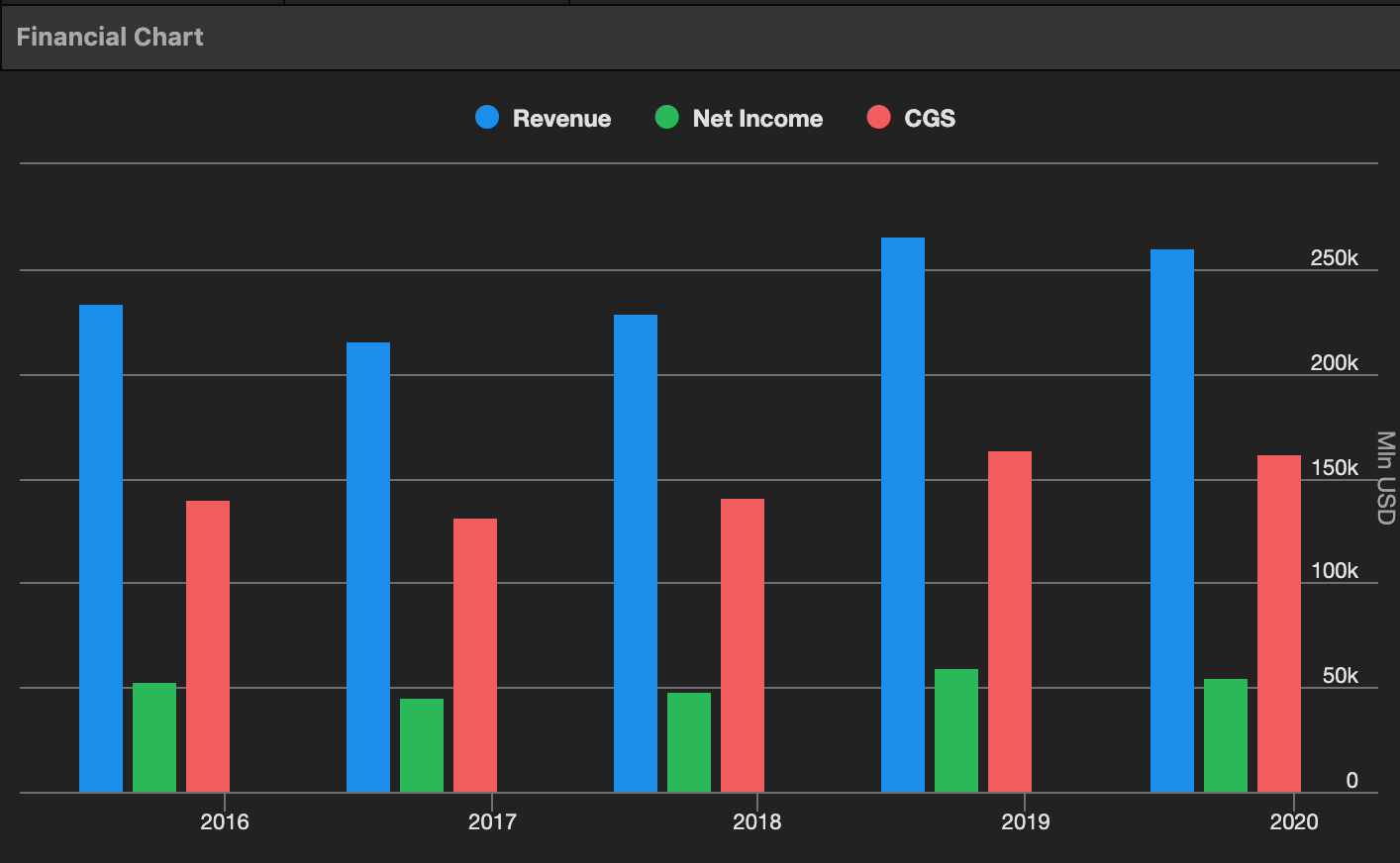

If you just look at the numbers (for which 2023 will be similar to 2022), it looks like Duluth’s revenue and EBITDA have been largely stagnant for 4-5 years. Yuck.

It is of course worth remembering all the stuff that happened during those years. First COVID (during which their retail stores were entirely shuttered), then supply chain disruptions, then a highly promotional competitive environment because peers forgot about the bullwhip effect and failed to manage inventory well into a softening macroeconomic environment. Duluth managed through this period reasonably well; they didn’t get over their skis on their inventory and they’ve actually made quite a bit of progress with becoming less promotional and having more full price selling (progress that has been masked by a much more promotional environment combined with rising costs for everything from materials to labor to shipping.)

At the same time, they’ve spent a lot of capex dollars on non-revenue-generating investments. Pre-COVID, they spent a lot of capex, but it was mostly on stores that generated nice 4-wall economics. In the wake of some growing pains (where they got a bit sloppy with inventory/discounting), as well as a global pandemic (which made people think twice about physical stores), they chose not to open stores. They do plan to return to opening stores, just fewer and more targeted ones.

But in the meanwhile, they’re still spending on capex - $55 million budget this year ($15 million more than EBITDA and fully 25% of their current market cap), on top of $30 million last year. That’s $80 million in capex (of which I estimate $60 million is discrete growth / non-maintenance capex) with zero dollars of incremental revenue or EBITDA to show for it. As far as anyone can tell, they are throwing money into an abyss, then chucking gasoline and lit matches after it.

What they did instead was build up their infrastructure. Again, remember that this business more than 6x’ed over the course of a decade, going from a sub-$100MM catalog business operating out of one warehouse to a nationwide chain of stores and fulfillment centers.

These investments included a web platform upgrade, Manhattan warehouse management systems, and the massive automated distribution center in Adairsville, GA (60 miles northwest of Atlanta.) This DC uses AutoStore RedLine technology - if you’ve ever been in a standard warehouse, it makes it a whole lot clearer what they mean by “automation.”

This facility will have the capability of handling 75% of their existing assortment and 60% of their existing volume. When I talked to them in June about the ROI on this facility, the answer is that there isn’t a direct ROI today (again, part of the market’s frustration.) Instead, they explained:

There are a number of value creators in the business case that play out over a 10 year period - this is a longer return on investment than a typical store where payback is two years - this [Adairsville] has a payback of 5-10 years - but that’s what we’re looking at is 5-10 years from now… to get the real return on that capital investment - you have to extrapolate out to the years where we can support a wholesale channel endeavor - we can support additional brands - and the leverage potential of Adairsville automation - the capacity that it’s giving us - those growth initiatives whereas today if we didn’t have that - we were already starting to stress the existing fulfillment centers in the way they manually pick, pack and ship and the people you can hire - so we see that the automation - yes, you get some near term variable expense leverage - but it’s an enabler of other growth channels.

They further noted that there are a lot of benefits that are not immediately quantifiable that will nonetheless allow them to leverage growth:

there is a model that says - incremental sales from new customers that retain at a higher rate - so if our - customer retention profile improves by 10 or 20 bps - that means those existing customers are going to spend a little more - and how we can serve those customers through faster delivery times, is part of that retention hook - having products that do get returned to us back into our inventory quicker - fewer clearance marks - and then there’s gross margin expansion - once we are really fully automated there in the location.

Wholesale is also not a pie-in-the-sky idea; they mentioned to me in June that it might be as soon as late 2024 that they start to scale that up. Even if it takes longer, I don’t think we’ll be waiting around forever.

They did confirm that this is the “hump year” for capex and while they will still have some projects around data, they expect significant free cash flow going forward.

So, if you woke up one day and forgot that SEC filings existed, and decided to just compare Duluth’s systems, infrastructure, promotional targeting, and so on to where it was five years ago, you would conclude it is a much better business. And it is - they just aren’t reaping the benefits yet.

They are not idiots. They are not making these investments for no reason. Considering his ownership, Schlecht is essentially spending his own money. He is not a young man (75) and has no real reason to pursue some wild goose chase at the expense of generating cash flow today. The company is building towards something.

In 2021, the company laid out its Big Dam Blueprint targeting $1 billion in sales and 14-15% Adj. EBITDA margins. I don’t think this is achievable by 2025 any longer, but 2030 isn’t out of the question.

The company continues to focus on organic new product introduction, and has a history of successful M&A of small brands - Alaskan Hardgear (now AKHG) was successfully scaled up into a nice little business. They’ve also had quite a bit of success with their wholesale pilot with Tractor Supply, now in 180 stores, up from 13 when they started in spring 2021 - admittedly a limited line of SKUs but also not in a store that’s a huge clothing destination.

The long and short of it is that right now, the PnL is burdened by a bunch of “enabler” scale investments that are not yet paying dividends. As another thought experiment, they have three DCs other than Adairsville, each a little over 200K square feet. Right now, they have all the fixed costs of the Adairsville facility but also all the fixed costs of the other facilities. Surely there’s millions of dollars of overhead and labor they could cut out by closing down or at least downsizing other facilities and moving volumes to Adairsville. Ditto this for the cost of various systems and teams they’ve implemented to get to a $1.5B scale but aren’t getting full use from yet.

Finally, we haven’t even talked about their advertising budget - they spend a low double digit percentage of revenue on advertising including national TV spots during sports and so on, compared to under 6% (i.e. half) for Columbia.

Growth investments through the PnL are always harder to think about than growth investments through capex, but I feel relatively confident that if they were running this business for cash rather than trying to build a billion-dollar brand, they could generate $50 - $60 million of EBITDA with perhaps $15 million of maintenance capex. That’s $30 million of free cash flow plus or minus some against a market cap of less than $250 million today, or a 12% “steady state” free cash flow yield (a metric I find useful to sometimes think about).

The hard part is building a brand, earning customer loyalty, coming up with innovative products. They’ve already done that. There is clear and obvious whitespace. Either they will find a way to get it to a billion dollars, or someone else will.

As another thought experiment (hypothetical, since I doubt the company is for sale) - imagine what results would be in 2 or 3 years if COLM or VFC bought DLTH and simply plugged their complementary, non-cannibalistic products into their existing distribution network. Could they increase revenues by 20%? 50%? What would the incremental margins on that be? Duluth trades for a paltry ~⅓ of revenues today and I have to imagine that a larger apparel company could probably double the EBITDA in relatively short order. Even at multi-year lows, COLM and VFC trade at ~1.2x revenue. I’m not saying that’s where Duluth should trade, but the point is that buying Duluth at double its current price would probably be a pretty sweet deal for a strategic acquirer. Again, this is just a hypothetical but I think it’s a put option - if we’re sitting here in 3-5 years and Schlecht is approaching 80 and they’re still floundering, wouldn’t it at least be on the table?

Valuation

Projecting numbers in the near term is too hard, so I’ve given up. I think about it bigger-picture. In the table below, the top row represents revenue. The left column represents EBITDA margins. The rest of the table represents the value of the stock under those numbers assuming zero interim cash flow.

You can pick your own numbers but it’s hard for me to believe that in five years, Duluth won’t be somewhere on this table. Even under the low scenario, it would be a respectable 20% CAGR. At the high end, the numbers start to get a little bit silly. The reason the stock is so beat up right now is a lack of free cash flow (due to the massive capex) and the lack of traction on either the top or the bottom line. It’s basically priced like an option at this point because people don’t believe they’ll ever see any value.

I’ve never seen a bigger disconnect between the public market’s perception (this is a terminally broken story) and how the management team feels (that they are on the path to a much larger and more efficient business.) I think I’ll leave with this quote from Sam Sato from the call last December:

We're going to prudently focus on managing expenses. Having said that, we're focused on unlocking the full potential long term. And so yes, there is some flexibility in our OpEx as we move into next year for sure but we're not going to necessarily cut our nose off to spite our face, meaning there are certain things that we believe we've got to invest in, in order for our business to scale and continue to grow sustainably long term. And that's largely around technology and logistics.

Duluth is currently in the no-man’s-land of having all the costs (and capex) of their investments, with none of the benefits. You have to be comfortable with the fact that they’re not going to window-dress quarter to quarter and they really are thinking long term, but I think we’re close to finally starting to unlock the benefits of the multi-year investments they have made.

I should add as a postscript that I'm usually a near-term EBITDA based investor. There are certain situations where I'm investing in something else - a brand that I am absolutely, positively convinced is worth a billion dollars (someday). Numbers might suck over the next 12 months, or even longer. That's not what I'm focused on. As painful as it might be, I think the long-term returns are worth it, in the context of a diversified portfolio with other investments with a nearer-term payoff profile.